Project

The migration of sharks and rays from the North Sea

There are 17 species of sharks and rays in the North Sea, including along the Dutch coast. Professional and recreational fishermen sometimes see these species in their catch, but little is known about these animals. A consortium of scientists, fishermen, policymakers and nature organizations now want to change that. We do this by tagging sharks and rays with transmitters. The transmitters collect data to gain more insight into the survival, distribution and migration of these unique animals.

Sharks and rays as a source of information

Sharks and rays are elasmobranchs i.e. cartilaginous fish. They are generally long-lived, slow-growing and late-maturing species. As a result, they are sensitive to fishing pressure, pollution and ecological changes in the environment, especially in spawning and nursery areas. Both for nature and fisheries management, more knowledge is needed about the migration and stock size of sharks and rays. This knowledge should lead to a scientific framework that underpins the further development of effective nature and fisheries management. The project is a collaboration between the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Rijkswaterstaat, Wageningen Marine Research, Wageningen University, Sportvisserij Nederland, the World Wildlife Fund, the Dutch Elasmobranch Association and VisNed.

The spatial distribution of sharks and rays can be studied at two levels. First of all, migration patterns can be examined at the level of the individual. We do this through the use of tags. Secondly, with the help of analyzes of spatial catch data, but also with DNA analyses, the distribution and stock size can be made clear per species. Combining this information creates an increasingly complete picture of shark and ray populations in the North Sea and in Dutch coastal waters.

Tracking individual sharks and rays with transmitters

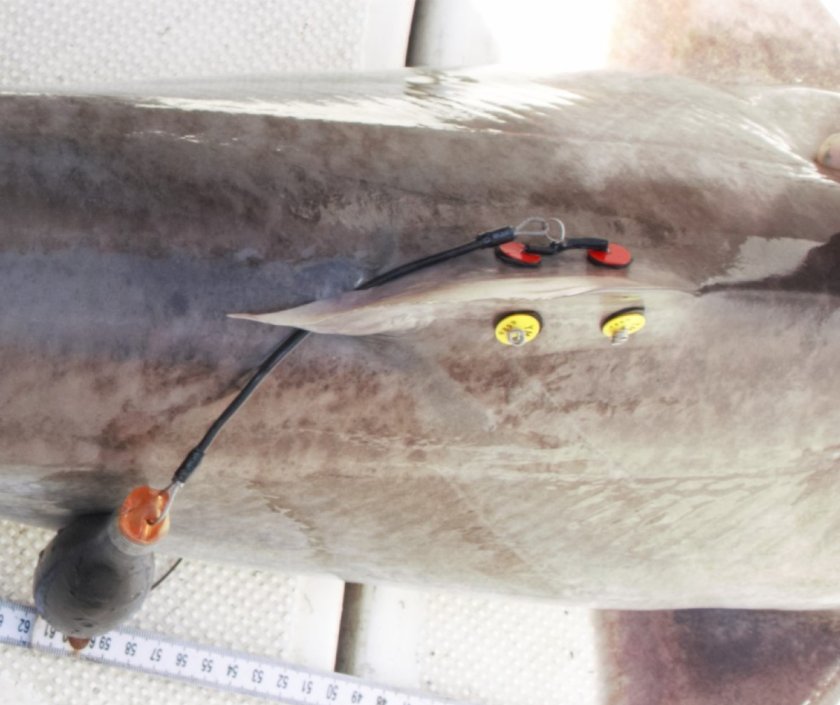

Pop-off satellite Data Storage Tags (PDST, MiniPats from WildLife Computers) are deployed to map the individual migration patterns of spotted smooth shark, tope shark and stingray (Fig. 1). These tags are placed on the shark's dorsal fin or on the ray's tail. The tags measure temperature and depth data every minute. After a year, these tags automatically detach from the fish. The tags then float to the surface of the water and broadcast all the data to the ARGOS satellite system. With the data obtained, it is possible to trace the migration pattern of the tagged animal in the North Sea. For this purpose, depth maps of the seabed and of local differences in the tidal cycle in the North Sea are used. Since 2019, 17 spotted smooth sharks and six stingrays have been fitted with a PDST transmitter.

In addition to the PDST tags, other tags, so-called Data-Storage Tags (DST) are also used to map the individual migration patterns of the spotted ray and blonde ray (Figure 2). As with the PDST, the DST records depth and ambient temperature at fixed intervals (10 seconds). These tags are programmed to release after 18 months and float to the sea surface to be carried to shore. Unlike PDST, data on the DST is not sent through the ARGOS satellite system, but the data is stored on the tag. These tags must therefore be found and reported back by, for example, the fishing industry or via beach walkers so that the stored data can be downloaded.

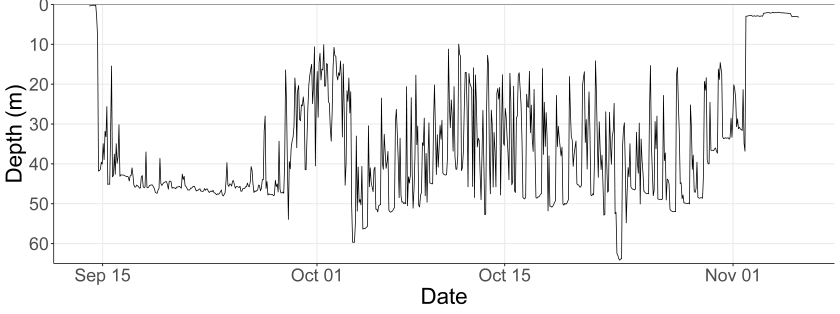

Since August 2021, 26 spotted rays and 25 blonde rays have been marked with a DST through intensive cooperation with the professional fisheries. This tag is attached to the tail (Figure 2). In the meantime, 8 tags have been returned, 6 of which were from DSTs found by walkers on the beach. So far, the most notable report has been the finding of a DST off the Danish coast from an 85cm blonde ray that was tagged in August near the English coast. The chart below shows the results of a female spotted ray tagged on September 14 just north of Ameland and recaptured on November 3 by fishermen near the east coast of England a few dozen miles from Great Yarmouth. In two months, the ray travelled almost 224 km. The graph shows the water depth at which the ray moved through the water column, with the sea surface at the top. As can be clearly seen, the ray is very active in its swimming movements through the water column. Such behavior was not yet known for this species.

Insights into populations with DNA

At the population level, efforts are also being made to map the possible genetic subpopulations of the spotted smooth-hound, thornback ray, spotted ray and blonde ray in the North Sea. For this, a small piece of tissue (finclip) is taken from a large number of individuals. This piece of tissue contains DNA, of which the genotype (genetic code) is subsequently determined. Possible subpopulations become visible by comparing the genotypes and finding whether groups are separated in space and time. This information makes it possible to visualize relationships and distinguish populations. Here too, the intensive cooperation between the fishing industry and research is indispensable because a large part of the DNA samples must be collected using fishing vessels; research vessels; and fish auctions.

So far, samples have been taken from 864 thornback rays, 401 blonde rays and 490 spotted rays. More samples will be taken in the coming months and the first results are expected in the autumn.

Follow-up

The research will continue in 2022 and then the hope is that tope sharks can be tagged with MiniPats in the Wadden area. Like the Oosterschelde, the area is a breeding ground for sharks where adult females, as well as juveniles, are caught in the area.

In addition, rays are still tagged with DSTs and samples are taken for DNA analysis. This gives us an increasingly clear picture of the life cycle of sharks and rays.