“The North Sea is one of the most productive seas in the world”

Fishers are perhaps the most ‘traditional’ users of the North Sea. But they’re also the group that will be most affected by the change from the old way of doing things to the new way. Especially now that wind farms and nature conservation are increasingly staking their claim to space in the North Sea.

- Unfortunately, your cookie settings do not allow videos to be displayed. - check your settings

Food transition

The bottom of the sea is where sole and plaice hide in the sand, and those two species are the main reason Dutch North Sea fishers head out to sea. “As much as 74 percent of the sole quota set by the EU is allocated to the Netherlands,” says Nathalie Steins, social scientist at Wageningen Marine Research. “Fishers also target species that swim in the water column, such as herring and mackerel. And then there are also the brown shrimp fishers and small-scale coastal fisheries.”

The North Sea flatfish fishers, when targeting sole, pull beam trawls to which tickler chains are attached across the seabed. That’s a type of fishing known as bottom trawling, and it’s easy to imagine how that can have a significant ecological impact. “But make no mistake: almost all fishing methods disturb the seabed,” says Steins. “The boards used to open the trawl nets that target pelagic species in the water column can also hit the seabed. Of course, fishing by definition has ecological impacts because you’re removing fish from the sea. Whether or not it’s sustainable depends entirely on how you design that fishery.”

Jaap van der Meer, a research associate at Wageningen Marine Research and professor by special appointment of Sustainable Marine Food Production at Wageningen University & Research, agrees. “The North Sea is one of the most productive seas in the world. It provides up to 5,000 kilos of fish per square kilometre every year.” The majority of that catch does not end up on Dutch plates: people in the Netherlands mostly eat canned tuna and Norwegian salmon. “Most of the sole goes to Italy, and the plaice to Belgium, Germany and France. The Netherlands is also a hub for processing and trading other fish species caught elsewhere. We’ve been able to establish ourselves in that position because we have an infrastructure of ports and fish auctions left over from the heyday of fishing here.”

The fishing industry contributes less than 1% to the Dutch gross domestic product, but is very important from a cultural point of view.

Financial struggles

That heyday is over. These days, the economic importance of the fishing industry is minimal. “The sector contributes less than 1 percent to the Dutch gross domestic product,” says Steins. “But the fishing industry is very important from a cultural point of view. Villages like Katwijk and Volendam still see themselves as fishing villages. Fishing is part of their identity.”

That aspect of it persists, even as the sector struggles financially. The problems the fishers are facing didn’t emerge overnight. “We’ve long had a Common Fisheries Policy in Europe to combat overfishing,” says Van der Meer. “The Netherlands no longer determines itself how much its fishers can catch. Europe sets quotas on how much of every species can be caught. The landing obligation is also a European regulation: if fishers catch fish that are too small, they have to land them.” This is supposed to encourage fishers to fish more selectively and not waste food by throwing fish back into sea, which most fish usually don’t survive.

On top of that regulatory burden came Brexit, which resulted in quota losses and makes it more difficult to fish in British waters. “And then came the ban on pulse fishing,” says Steins. “That’s a technique in which the flatfish are startled with electric pulses, causing them to emerge out of the sand and swim into the net. It’s less disruptive to the seabed than beam trawling and uses much less fuel, yet the method has been banned by Brussels, mainly for political reasons. But for fishers who had invested in this method, it was a disaster.”

A decommissioning scheme was recently implemented to buy out fishers who want to quit. Steins and Van der Meer estimate that the Netherlands now only has about 30 remaining large beam trawlers. “And now there are going to be geographic restrictions for fishers too,” says Van der Meer. “As part of the North Sea transition, large areas of the sea are being set aside for wind farms and nature reserves.”

Wind farms as nurseries

Wind farms are quite literally obstacles for fishers. “As with oil platforms, fishers need to keep at least 500 metres away from a wind farm,” says Steins. “These rules do differ from country to country, with fishers allowed into the UK’s wind farms, for example. When you consider how many more wind farms are still being planned, it inevitably will mean less space for fishermen.”

And what about the fish that are of commercial interest to fishers? Wageningen Marine Research is involved in numerous studies on the effects of wind farms on marine life. “We’ve mainly studied the direct impacts,” says Van der Meer. “For example, we’ve looked at the pile driving involved in constructing a wind park and the likelihood of birds and bats crashing into the turbines. The methods we use for those studies include models and laboratory experiments.”

More follow-up research still needs to be done to look at the indirect effects. “That’s mainly about how fish behave around an operational wind farm,” says Van der Meer. “Or how the presence of such structures in the sea affects the wind field, currents and the re-suspension and deposition of silt and sand. It may have implications for phytoplankton, and scientists are now working on initial modelling studies.”

While there’s still no clear picture of the ecological impacts of offshore wind farms, Van der Meer is already prepared to draw at least one conclusion. “None of the studies have produced any really shocking findings. That might change if the proportion of wind farms in the North Sea increases, but overall the ecological effects are still modest right now.”

Wind farms could even be good for fish stocks if they can act as nurseries for young fish. Wageningen Marine Research has conducted research on artificial reefs constructed at the Borssele 1 and 2 wind farms off the coast of Zeeland. “Cod and sea bass were tagged to monitor their movements,” says Steins. “Cod appear to enjoy hanging around such reefs. Sea bass don’t seem to take much notice of wind farms.”

Controversy

Setting aside swathes of the North Sea as a nature reserve further limits the options available to fishers. Nature conservation organisations are calling for 30 percent of the North Sea to be designated a nature reserve so that the ecosystem can remain healthy. “That hasn’t happened yet, but there are Natura2000 areas, such as Dogger Bank, the Central Oyster Grounds and the Frisian Front,” says Steins. “There’s no absolute ban on fishing there yet. Each of those areas has its own rules and regulations.”

The struggles that fishers are experiencing now aren’t primarily caused by fish stocks.

It’s obviously essential for ‘nature’ to be given space in the North Sea too, but fish stocks are not currently under pressure from overfishing. “The pressure exerted by the fishing industry started to increase in the 1960s,” says Van der Meer. “There was persistent upscaling in the sector, with larger, more efficient vessels, and the processing of fish being performed straight away while still at sea. The Netherlands was at the forefront of that development. In the 1990s, populations of plaice in particular collapsed, later followed by cod. That’s when the Common Fisheries Policy was taken up in earnest. We learned our lesson and the populations of most fish species have since recovered. Not all of them, though. Cod, for example, hasn’t fared well. But the struggles that fishers are experiencing now aren’t primarily caused by fish stocks.”

The upscaling of fisheries doesn’t necessarily have to lead to overfishing. “If you regulate, enforce and monitor fishing properly, you should be able to design it in a way that keeps it sustainable,” says Steins. And while there sometimes seem to be ‘parallel realities’ in the perceptions of fishers and EU regulators, there’s also little opposition to European quotas among fishers themselves. “Current debates are about unwanted by-catch and about which stretches of the North Sea are going to become nature reserves. Fishers would of course prefer to fish in the most abundant areas, but these are the same areas that nature organisations want to protect.”

Conservationists point to the importance of protected areas at the North Sea, and fishers swear by good fisheries management.

“There’s a kind of controversy going on, with conservationists pointing to the importance of protected areas, and fishers swearing by good fisheries management,” says Van der Meer. “Here at Wageningen Marine Research our position is that we really need to do much more research on this.”

Aquaculture

Overall, how do the researchers see the future of North Sea fisheries? “Further changes to fishing fleets seem inevitable,” says Steins. “It’s important for the industry to innovate, for example by switching to more energy-efficient vessels.” Van der Meer adds: “We’re also seeing changes in the species found in the North Sea: squid, langoustines, red gurnard and mullet are on the rise. This could be related to climate change, though we can’t be sure just yet. But it’s something you could adjust your fleet and fishing methods to.”

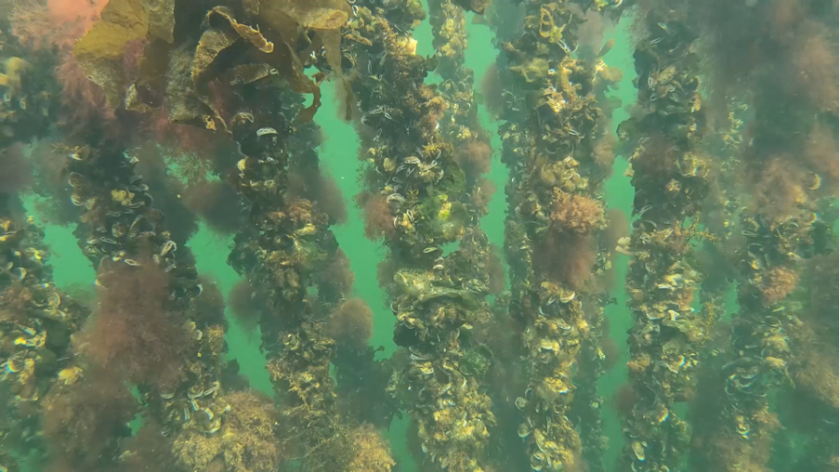

Any conversation about a food transition needs to include not just the fishing industry but also aquaculture, such as the cultivation of seaweed, mussels and oysters, possibly as part of a wind farm. “Experiments are being conducted using suspended cultures for mussels,” says Van der Meer. “These are depth-adjustable structures that you can sink into wind farms. People have been talking about 14,000 square kilometres of seaweed cultivation in the North Sea. That’s impossible, but we still need to find out what could be feasible. We’ve now launched several studies into the ecological carrying capacity of aquaculture.”

Steins stresses that more research is also needed on interactions between fish stocks, such as cod and herring. “Everything is interconnected in an ecosystem. As researchers, we study the North Sea as a single ecosystem; we obviously don’t limit ourselves to territorial waters. Ultimately, the knowledge we build ought to contribute to an ecosystem-based fisheries policy for the entire North Sea.”

At the end of the day, we humans are also part of the ecosystem.

And that requires research not just into the behaviour of fish, but also into the behaviour of fishers themselves. “How are they dealing with all the changes?” says Steins. “What choices do they make when they’re out at sea, where do they go when an area is closed off? And how does that affect their operational management and the ecology of the North Sea? As a social scientist, that’s something I’m particularly interested in. We look not just at ecological effects, but also at socio-ecological impacts. Because at the end of the day, we humans are also part of the ecosystem.”